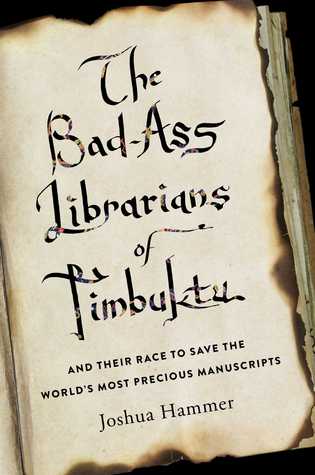

The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu: And Their Race to Save the World’s Most Precious Manuscripts by Joshua Hammer

The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu: And Their Race to Save the World’s Most Precious Manuscripts by Joshua Hammer Formats available: hardcover, ebook, audiobook

Pages: 288

Published by Simon & Schuster on April 19th 2016

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

To save precious centuries-old Arabic texts from Al Qaeda, a band of librarians in Timbuktu pulls off a brazen heist worthy of Ocean’s Eleven.

In the 1980s, a young adventurer and collector for a government library, Abdel Kader Haidara, journeyed across the Sahara Desert and along the Niger River, tracking down and salvaging tens of thousands of ancient Islamic and secular manuscripts that had fallen into obscurity. The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu tells the incredible story of how Haidara, a mild-mannered archivist and historian from the legendary city of Timbuktu, later became one of the world’s greatest and most brazen smugglers.

In 2012, thousands of Al Qaeda militants from northwest Africa seized control of most of Mali, including Timbuktu. They imposed Sharia law, chopped off the hands of accused thieves, stoned to death unmarried couples, and threatened to destroy the great manuscripts. As the militants tightened their control over Timbuktu, Haidara organized a dangerous operation to sneak all 350,000 volumes out of the city to the safety of southern Mali.

Over the past twenty years, journalist Joshua Hammer visited Timbuktu numerous times and is uniquely qualified to tell the story of Haidara’s heroic and ultimately successful effort to outwit Al Qaeda and preserve Mali’s—and the world’s—literary patrimony. Hammer explores the city’s manuscript heritage and offers never-before-reported details about the militants’ march into northwest Africa. But above all, The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu is an inspiring account of the victory of art and literature over extremism.

My Review:

April 10-16 is National Library Week, so The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu was an absolutely irresistible title to review this week.

But the story in this book is a lot bigger than just the librarians, and goes a lot further back. Yes, we do have the story of the librarians who rescued the manuscripts, but also a whole lot more. Because the author has taken the story and set it into the history of the region, and provides the context for why the rescue was necessary.

So, this isn’t just the story of the librarians or the rescue. What we have is a history of Timbuktu and the region surrounding it. The author gives us an all too brief glimpse into the scholarly past of the town, and shows how this incredible treasure trove of manuscripts came to be in this city that is a byword for remote.

From the late 13th century through the early 20th, Timbuktu survived successive cycles of open and abundant scholarship, followed by waves of educational repression and suppression. When the scholarship flourished, manuscripts were collected and accumulated by the thousands. During the periods of repression, the manuscripts were hidden in private collections in the city and surrounding areas.

In the 20th century, a man named Abdul Kader Haidara inherited one of the largest of those private collections. He went from being skeptical about his legacy, to becoming a passionate preserver of not only his own archive, but of all of the manuscripts and scrolls that had been hidden, both in the town and in the large area surrounding it.

For decades, Abdul Kader sought grant funds, and eventually was able to create a world-renowned institute for the study and preservation of the manuscripts, said to number nearly 800,000 and nearly all irreplaceable.

But just as in history, his wave of open scholarship was succeeded by a wave of severe repression. In the 21st century, Al Queda and other intolerant forces began to scoop up territory around Timbuktu, as they inserted themselves into the power vacuum after the fall of Qaddafi. When an Al Queda offshoot took control of Timbuktu, Abdul Kader made plans for the manuscripts.

In a long and daring series of convoys, over desert trails and river voyages, and through military checkpoints that had to be bribed or evaded every step of the way, 95% of the precious manuscripts were evacuated to safety.

This is their story.

Reality Rating B: I’m not sure whether to call this one a “Reality” rating or an “Escape” rating. The story is real, but the manuscripts escaped.

This is really three stories rolled into one – first the history that made this collection possible. Second, the tragedy that made the rescue necessary. And finally, the rescue itself.

While the history of Timbuktu and its frequent scholarly golden ages was interesting, the recent history was sometimes hard to follow. While we know in general terms that many of the Islamic fundamentalist sects are extremely hostile towards any historical references that contradict their dogmatic view of history and religion, the attempt to provide the reader with context on which group controlled which part of Mali at which time, and why, often fell a little flat. There were too many names and dates, and not enough background to what made them different from each other.

History, or at least the parts of it that interest this reader, is about people. There were too many unfamiliar names and places infodumped on the reader in too few pages. At the same time, those expositions felt longer than the earlier history, or certainly dragged on longer than the story of Abdul Kader and the rescue of the manuscripts, itself.

It is in Abdul Kader’s story that the book really shines. We are with him as he shoulders the responsibility for his family’s collection, and we suffer along with all of his hardships on his dangerous and ultimately successful trips to acquire more manuscripts for the Institute that set him on his path. It’s his journey, his hopes, and his fears that bring the reader fully into this story and engage the mind, heart and imagination.

Speaking as a librarian, Abdul Kader’s story is one that makes me proud of my profession. He’s a librarian, a rescuer of history, and an inspiration to us all.

The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America by

The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and the Politics of Race in America by  Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World by

Data and Goliath: The Hidden Battles to Collect Your Data and Control Your World by  Freedom of Speech: Mightier Than the Sword by

Freedom of Speech: Mightier Than the Sword by  Even though this is

Even though this is  Patience and Fortitude: Power, Real Estate, and the Fight to Save a Public Library by

Patience and Fortitude: Power, Real Estate, and the Fight to Save a Public Library by