The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann

The Wager: A Tale of Shipwreck, Mutiny and Murder by David Grann Narrator: Dion Graham

Format: eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via Edelweiss, supplied by publisher via Libro.fm

Formats available: hardcover, paperback, large print, ebook, audiobook

Genres: history, nonfiction, true crime

Pages: 352

Length: 8 hours and 28 minutes

Published by Doubleday Books, Random House Audio on May 11, 2023

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org, Better World Books

Goodreads

From the international bestselling author of KILLERS OF THE FLOWER MOON and THE LOST CITY OF Z, a mesmerising story of shipwreck, mutiny and murder, culminating in a court martial that reveals a shocking truth. On 28th January 1742, a ramshackle vessel of patched-together wood and cloth washed up on the coast of Brazil. Inside were thirty emaciated men, barely alive, and they had an extraordinary tale to tell. They were survivors of His Majesty’s ship The Wager, a British vessel that had left England in 1740 on a secret mission during an imperial war with Spain. While chasing a Spanish treasure-filled galleon, The Wager was wrecked on a desolate island off the coast of Patagonia. The crew, marooned for months and facing starvation, built the flimsy craft and sailed for more than a hundred days, traversing 2,500 miles of storm-wracked seas. They were greeted as heroes. Then, six months later, another, even more decrepit, craft landed on the coast of Chile. This boat contained just three castaways and they had a very different story to tell. The thirty sailors who landed in Brazil were not heroes – they were mutineers. The first group responded with counter-charges of their own, of a tyrannical and murderous captain and his henchmen. While stranded on the island the crew had fallen into anarchy, with warring factions fighting for dominion over the barren wilderness. As accusations of treachery and murder flew, the Admiralty convened a court martial to determine who was telling the truth. The stakes were life-and-death—for whomever the court found guilty could hang.

My Review:

Fiction has to be plausible, while nonfiction just has to be true. The story of HMS Wager – or more properly the story of her doomed voyage, disastrous wreck and the against all odds recovery of even a fraction of her crew – is so far over the top that we might not accept it as fiction – except possibly as sheer horror. That this voyage, and all of the extremes the crew passed through and even survived in the tiniest part, really happened carries the reader forward with them even when the conditions are so harrowing that many will want to turn their eyes away.

But man’s inhumanity to man – even without the type of disastrous conditions the crew of the Wager endured – is an oft told tale and not just of the sea. What carries this over the top is its denouement. Not just that some survived to be rescued, but that of those survivors, only ten men out of the original company of nearly three hundred lived to tell the tale. And they all seemed to tell entirely different tales, each attempting to justify their actions after the ship wrecked off the coast of present-day Chile.

The crew of the Wager mutinied after the terrible wreck. The Captain wanted to go forward with their original mission, in spite of having lost, at that point, 2/3rds of his crew, his ship, and quite possibly both his authority and a piece of his mind. One natural leader, the gunner John Bulkley, had a plan for navigating the Straits of Magellan in one of the smaller boats remaining to the castaways. Bulkley had drive, the trust of more of the men, a plan and a clear direction for safety, while Captain Cheap only had waning authority and wrecked trust.

Bulkley and his contingent sailed east. Cheap and his loyalists sailed west. Both returned home, with vastly differing accounts of the terrible events that took place on what the castaways had dubbed ‘Wager Island’. The court martial should have been epic – and it should have decided the truth – or at least a truth – for posterity.

But the jury on precisely what happened on Wager Island, whether the mutiny was justified or was even, technically, a mutiny at all isn’t even out because it never went in. The Admiralty chose not to pursue any of the possible charges against anyone who returned, outside of assigning blame for the wrecking of the Wager herself. Not because there were no charges to answer, but because those answers would have shot cannonballs through the British Navy’s reputation and its justifications for its so-called ‘civilizing’ conquests that do not hold up to the light of day now.

And clearly didn’t then, either, even if the Admiralty refused to acknowledge it.

Reality Rating A: The Wager is a terrible story told terribly, terribly well, made even better by the excellence of the voice narration by Dion Graham. His voice carried me through a story that, while compelling, was so very dark – all the more so for being a true story – that I would have turned aside without him.

There are three parts to The Wager’s epic narrative. It begins with the runup to the expedition that HMS Wager was intended to be a small part of. It reads as doomed from the beginning, an endless delay of money and bureaucracy, intending to be a salvo in a made-up war (the War of Jenkins’ Ear). The mission as a whole ended in a kind of pyrrhic victory, but by then the Wager had long since wrecked.

The heart – and heartbreak – of the story is in the conditions on Wager Island. Conditions that quickly break down into a chaos of failed discipline and desperation that recalls The Lord of the Flies. Not that conditions aboard HMS Wager weren’t desperate before the wreck, but the privation they had already experienced made the starvation, madness and despair while castaways just that much more difficult to bear.

As I listened to Dion Graham’s marvelous voice, the story kept building and building its recital of how truly awful the situation was, to the point where it reminded me of the privations described in Emma Donoghue’s Haven – without nearly as much reference to religion or G-d. By the time they left the island, there was no G-d to be found – no matter how much Bulkley searched for one.

What fascinated me was the rescue – or rescues as it turned out – and just how much the story morphed and changed when exposed to the light of ‘grub street’ journalism. There is very little ‘truth’ to be found by the time the conflicting accounts of the survivors and the even more sensational exaggerations of the press came into play. This is a story that leaves more questions than answers. Humans do not make reliable eyewitnesses – particularly in cases where each has a stake in saving their own skins – or necks.

The Wager isn’t the kind of adventure on the high seas that many of her crew read before they undertook the voyage. It’s an ultimately riveting, desperately tragic, terribly contentious account of a walk – or rather a sail – through the darkest places of men’s hearts and souls. A tale from which it is impossible to turn one’s eyes away, no matter how much one might be tempted to step aside. Which is only fitting, as the crew of HMS Wager could not either.

The New Guys: The Historic Class of Astronauts That Broke Barriers and Changed the Face of Space Travel by

The New Guys: The Historic Class of Astronauts That Broke Barriers and Changed the Face of Space Travel by  Just as Tom Wolfe’s

Just as Tom Wolfe’s  The story of The New Guys takes the TFNG from their earliest dreams of space to the ends of their careers. But there’s a wider context to the story of the space program as a whole, placing this book in the center between the machismo of Wolfe’s

The story of The New Guys takes the TFNG from their earliest dreams of space to the ends of their careers. But there’s a wider context to the story of the space program as a whole, placing this book in the center between the machismo of Wolfe’s  Books Promiscuously Read: Reading as a Way of Life by

Books Promiscuously Read: Reading as a Way of Life by  The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World by

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World by  Modern Loss: Candid Conversation About Grief. Beginners Welcome. by

Modern Loss: Candid Conversation About Grief. Beginners Welcome. by

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy by

We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy by  I came to this book via multiple odd routes. I heard the author speak a couple of years ago, because my husband really likes his writing. While it doesn’t resonate with me quite the same way, when it does, it really, really does. Coates’ comment at the beginning of

I came to this book via multiple odd routes. I heard the author speak a couple of years ago, because my husband really likes his writing. While it doesn’t resonate with me quite the same way, when it does, it really, really does. Coates’ comment at the beginning of  Format read: hardcover provided by the publisher

Format read: hardcover provided by the publisher Format read: eARC provided by the publisher via Edelweiss

Format read: eARC provided by the publisher via Edelweiss Apollo 8 by

Apollo 8 by

Dear Fahrenheit 451: A Librarian's Love Letters and Break-Up Notes to the Books in Her Life by

Dear Fahrenheit 451: A Librarian's Love Letters and Break-Up Notes to the Books in Her Life by  Her letter to

Her letter to  While her letter to Fahrenheit 451 is the author’s chance to talk about book challenges and book bans, many of her other letters and comments get into some of the nitty gritty of being a librarian surrounded by books. And involves some of the things that librarians have to do to maintain the libraries that surround them. Her letters to and about books that she is weeding, and the reasons that it may be time for some books to go, speak directly to the librarian in all book lovers.

While her letter to Fahrenheit 451 is the author’s chance to talk about book challenges and book bans, many of her other letters and comments get into some of the nitty gritty of being a librarian surrounded by books. And involves some of the things that librarians have to do to maintain the libraries that surround them. Her letters to and about books that she is weeding, and the reasons that it may be time for some books to go, speak directly to the librarian in all book lovers.

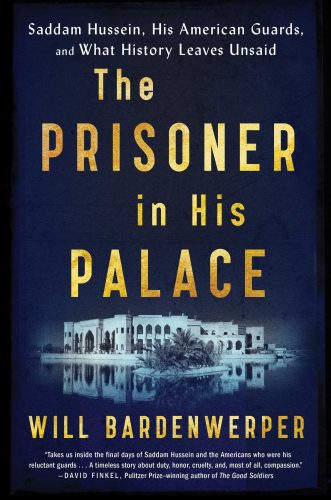

The Prisoner in His Palace: Saddam Hussein, His American Guards, and What History Leaves Unsaid by

The Prisoner in His Palace: Saddam Hussein, His American Guards, and What History Leaves Unsaid by