The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World by Stephen Brusatte

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World by Stephen Brusatte Format: eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via Edelweiss

Formats available: hardcover, paperback, ebook, audiobook

Genres: dinosaurs, nonfiction, science

Pages: 416

Published by William Morrow on April 24, 2018

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

"THE ULTIMATE DINOSAUR BIOGRAPHY," hails Scientific American: A sweeping and revelatory new history of the age of dinosaurs, from one of our finest young scientists.

"This is scientific storytelling at its most visceral, striding with the beasts through their Triassic dawn, Jurassic dominance, and abrupt demise in the Cretaceous." — Nature

The dinosaurs. Sixty-six million years ago, the Earth’s most fearsome creatures vanished. Today they remain one of our planet’s great mysteries. Now The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs reveals their extraordinary, 200-million-year-long story as never before.

In this captivating narrative (enlivened with more than seventy original illustrations and photographs), Steve Brusatte, a young American paleontologist who has emerged as one of the foremost stars of the field—naming fifteen new species and leading groundbreaking scientific studies and fieldwork—masterfully tells the complete, surprising, and new history of the dinosaurs, drawing on cutting-edge science to dramatically bring to life their lost world and illuminate their enigmatic origins, spectacular flourishing, astonishing diversity, cataclysmic extinction, and startling living legacy. Captivating and revelatory, The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs is a book for the ages.

Brusatte traces the evolution of dinosaurs from their inauspicious start as small shadow dwellers—themselves the beneficiaries of a mass extinction caused by volcanic eruptions at the beginning of the Triassic period—into the dominant array of species every wide-eyed child memorizes today, T. rex, Triceratops, Brontosaurus, and more. This gifted scientist and writer re-creates the dinosaurs’ peak during the Jurassic and Cretaceous, when thousands of species thrived, and winged and feathered dinosaurs, the prehistoric ancestors of modern birds, emerged. The story continues to the end of the Cretaceous period, when a giant asteroid or comet struck the planet and nearly every dinosaur species (but not all) died out, in the most extraordinary extinction event in earth’s history, one full of lessons for today as we confront a “sixth extinction.”

Brusatte also recalls compelling stories from his globe-trotting expeditions during one of the most exciting eras in dinosaur research—which he calls “a new golden age of discovery”—and offers thrilling accounts of some of the remarkable findings he and his colleagues have made, including primitive human-sized tyrannosaurs; monstrous carnivores even larger than T. rex; and paradigm-shifting feathered raptors from China.

An electrifying scientific history that unearths the dinosaurs’ epic saga, The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs will be a definitive and treasured account for decades to come.

My Review:

The dinosaurs may be dead, but the study of the dinosaurs is downright lively, at least according to this book.

Or to put it another way, if your kid really, really, really loves dinosaurs, there’s a chance he’ll become a bit like the author of this book – at least in his enthusiasm for his subject. And that’s a good thing – even if it may be driving you crazy at the moment.

Just as elephants and polar bears are the charismatic megafauna of the 21st century, dinosaurs fill that same space in the popular imagination as representatives of, well, the Jurassic period of prehistory. There are even dinosaur analogs for those two species, with the horned triceratops filling the plant-eater niche while there is no better representative for carnivores than the tyrannosaurus rex – the great lizard king of the dinosaurs.

We all recognize them, and many other dinosaurs, because those great beasts, their impressive rise and their sudden and thunderous fall, have captured the popular imagination.

This book is both the story of one relatively young paleontologist, and to a significant extent the experiences and enthusiasms that made him into the scientist that he is today.

And it is also the story of the rise of the dinosaurs from one species among many all the way back in the Triassic period, through their apex as the dominant species on this planet, to their sudden and catastrophic elimination at the hands – or rather the crash – of a massive asteroid.

It is their demise that eventually led to us. Unlike the fictional world of The Flintstones comics, man and dinosaur never occupied this planet together – but we live with their descendants.

Reality Rating B: Every once in a while I pick up a popular science book, if it is about a topic that interests me. A long time ago I listened to the audio of Wonderful Life by Stephen Jay Gould, about another great proliferation of species that are no longer among us. It’s from the period before the dinosaurs begin their long rise, but the books remind me of each other a bit.

There are both written in a popular style, intended to be read by an educated layperson. One doesn’t need to be a scientist, or even an aficionado, to get the point of that book. Or this one.

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs is an exploration, based on the science that is now known, of the conditions that gave rise to these iconic beasts, the world in which they lived and the contemporaries against whom they fought for dominance.

They didn’t come out of nowhere, and the author does a good job of introducing readers to the evolution that created them, and the evolution that allowed them to become the dominant life on earth. That they no longer are is fate, or chance, or karma, or destiny. Just as Monty Python chanted that “no one expects the Spanish Inquisition”, no one expects the planet to get whacked by a giant meteor – at least until it happens.

There’s a lot to love in this book, especially if you’ve never gotten over your fascination with dinosaurs – as it seems that no paleontologist ever does. There’s plenty of history to sink into, both the history of the dinosaurs and the history of the finding and figuring out about the dinosaurs.

At the same time, there’s also more than a bit of name-dropping about well-known paleontologists and their discoveries. The discoveries are always fascinating, but we don’t get quite enough about the individuals for them to stick in the mind.

In the end, it’s the dinosaurs themselves that stand out. Or fly. The idea that modern-day birds are themselves the last of the dinosaurs is an arresting idea. One that will make non-scientist readers look at our feathered friends in a whole new way.

All the Ever Afters: The Untold Story of Cinderella’s Stepmother by

All the Ever Afters: The Untold Story of Cinderella’s Stepmother by

Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker by

Hiddensee: A Tale of the Once and Future Nutcracker by  A Casualty of War (Bess Crawford #9) by

A Casualty of War (Bess Crawford #9) by  I have loved this series from its very beginning in

I have loved this series from its very beginning in  So the mystery in A Casualty of War had its anticlimactic moments, and also resembled bits of

So the mystery in A Casualty of War had its anticlimactic moments, and also resembled bits of  Forty Autumns: A Family's Story of Courage and Survival on Both Sides of the Berlin Wall by

Forty Autumns: A Family's Story of Courage and Survival on Both Sides of the Berlin Wall by  The Daughters of Ireland by

The Daughters of Ireland by  In this second book in the

In this second book in the  The person she becomes after it all crashes down around her is much more interesting, and much more capable, than anyone imagined – including Celia herself. Her transformation carries the reader along from London to Ballynakelly to Johannesburg, and it’s the making of her.

The person she becomes after it all crashes down around her is much more interesting, and much more capable, than anyone imagined – including Celia herself. Her transformation carries the reader along from London to Ballynakelly to Johannesburg, and it’s the making of her. Cat Shining Bright (Joe Grey #20) by

Cat Shining Bright (Joe Grey #20) by  The bright and shining thread revolves around talking feline detective Joe Grey, his tabby lady Dulcie, and their three kittens, born at the very beginning of the book (also at the very end of the previous book,

The bright and shining thread revolves around talking feline detective Joe Grey, his tabby lady Dulcie, and their three kittens, born at the very beginning of the book (also at the very end of the previous book,  If the idea of a story featuring a sentient (and often smart-alecky) cat sounds like catnip to you, start with Joe Grey’s first adventure,

If the idea of a story featuring a sentient (and often smart-alecky) cat sounds like catnip to you, start with Joe Grey’s first adventure,  The fates and futures of the kittens are tied up in prophecies made the wise old cat Misto near his end, during Cat Shout for Joy. Misto’s wisdom and the kittens various powers are tied in with the feral speaking cats at the old Pamillon Estate, with the ancient past of the speaking cats, and with the events of The Catsworld Portal and an earlier book in Joe Grey’s series,

The fates and futures of the kittens are tied up in prophecies made the wise old cat Misto near his end, during Cat Shout for Joy. Misto’s wisdom and the kittens various powers are tied in with the feral speaking cats at the old Pamillon Estate, with the ancient past of the speaking cats, and with the events of The Catsworld Portal and an earlier book in Joe Grey’s series,  Map of the Heart by

Map of the Heart by  I picked up Map of the Heart because I absolutely adored last year’s

I picked up Map of the Heart because I absolutely adored last year’s  The Painted Queen by

The Painted Queen by  If any of the above, or what follows, sounds like your cup of tea, do not, I beg you, start with The Painted Queen. It is the end of a saga that has been going on for over 40 years. Begin with

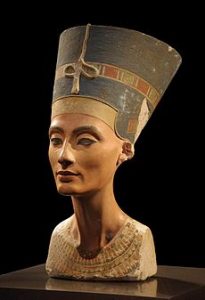

If any of the above, or what follows, sounds like your cup of tea, do not, I beg you, start with The Painted Queen. It is the end of a saga that has been going on for over 40 years. Begin with  There are, as was often the case in Amelia’s history, two stories going on. One involves both the history of early 20th century Egypt and early 20th century Egyptian archaeological history. As this story takes place in 1912, events are also part of the run up to World War I and the beginning of the end for both the British and the Ottoman empires. At the same time, the finding of Nefertiti’s bust was a real historical event, an event at which the Emersons were not present, so their involvement in the mess has to be tidied over by the author before the end, so that history can proceed on the course we know that it did.

There are, as was often the case in Amelia’s history, two stories going on. One involves both the history of early 20th century Egypt and early 20th century Egyptian archaeological history. As this story takes place in 1912, events are also part of the run up to World War I and the beginning of the end for both the British and the Ottoman empires. At the same time, the finding of Nefertiti’s bust was a real historical event, an event at which the Emersons were not present, so their involvement in the mess has to be tidied over by the author before the end, so that history can proceed on the course we know that it did. Sons and Soldiers: The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned with the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler by

Sons and Soldiers: The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned with the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler by