The Eagle Has Landed: 50 Years of Lunar Science Fiction by Neil Clarke

The Eagle Has Landed: 50 Years of Lunar Science Fiction by Neil Clarke Format: eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via Edelweiss

Formats available: paperback, ebook

Genres: anthologies, science fiction, short stories, space opera

Pages: 600

Published by Night Shade on July 16, 2019

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

The lone survivor of a lunar crash, waiting for rescue in a solar powered suit, must keep walking for thirty days to remain in the sunlight keeping her alive . . . life as an ice miner turns ugly as the workers’ resentment turns from sabotage to murder . . . an astronaut investigating a strange crash landing encounters an increasing number of doppelgangers of herself . . . a nuclear bomb with a human personality announces to a moon colony that it will soon explode . . . hundreds of years in the future, art forgers working on the lunar surface travel back in time to swap out priceless art, rescuing it from what will become a destroyed Earth . . .

On July 20, 1969, mankind made what had only years earlier seemed like an impossible leap forward: Apollo 11 became the first manned mission to land on the moon, and Neil Armstrong the first person to step foot on the lunar surface. While there have only been a handful of new missions since, the fascination with our planet’s satellite continues, and generations of writers and artists have imagined the endless possibilities of lunar life.

The Eagle Has Landed collects the best stories written in the fifty years since mankind first stepped foot on the lunar surface, serving as a shining reminder that the moon is a visible and constant example of all the infinite possibility of the wider universe.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Bagatelle by John Varley The Eve of the Last Apollo by Carter Scholz The Lunatics by Kim Stanley Robinson Griffin’s Egg by Michael Swanwick A Walk in the Sun by Geoffrey A. Landis Waging Good by Robert Reed How We Lost the Moon by Paul McAuley People Came From Earth by Stephen Baxter Ashes and Tombstones by Brian Stableford Sunday Night Yams at Minnie and Earl’s by Adam Troy Castro Stories for Men by John Kessel The Clear Blue Seas of Luna by Gregory Benford You Will Go to the Moon by William Preston SeniorSource by Kristine Kathryn Rusch The Economy of Vacuum by Sarah Thomas The Cassandra Project by Jack McDevitt Fly Me to the Moon by Marianne J. Dyson Tyche and the Ants by Hannu Rajaniemi The Moon Belongs to Everyone by Michael Alexander and K.C. Ball The Fifth Dragon by Ian McDonald Let Baser Things Devise by Berrien C. Henderson The Moon is Not a Battlefield by Indrapramit Das Every Hour of Light and Dark by Nancy Kress In Event of Moon Disaster by Rich Larson

My Review:

Just in time for the 50th Anniversary of Apollo 11 comes The Eagle Has Landed, a collection of stories, set on the Moon, that were written sometime AFTER that historic voyage.

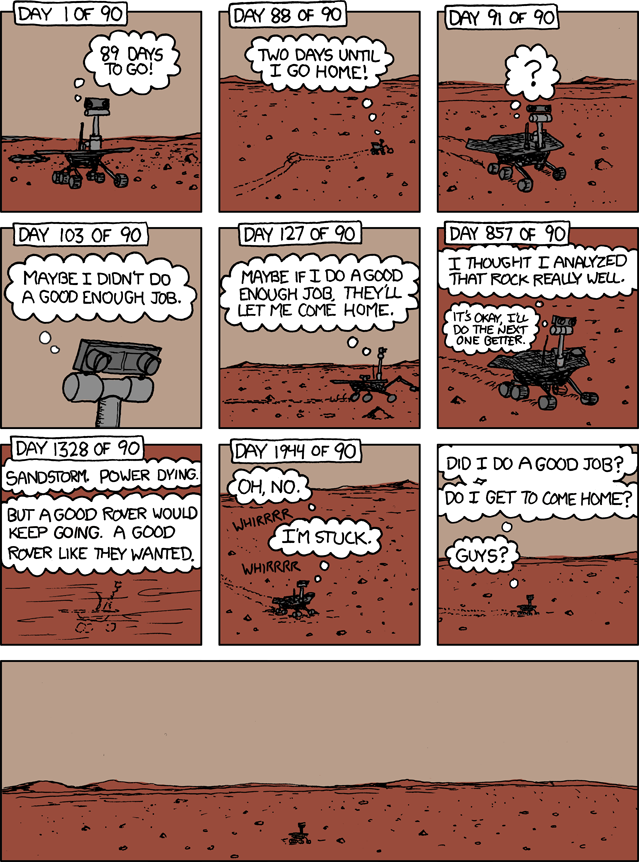

One of the interesting things, at least from the editor’s perspective, is how relatively few lunar-set stories there actually were, particularly in the immediate post-Apollo years. His speculation is that changing the first lunar landing from fiction to history moved lunar-set stories too close to a potential and seemingly reachable very-near-future pushed the concept out of science fiction.

And while we know from the perspective of hindsight that Apollo 11’s achievement marked the beginning of the end rather than the end of the beginning that we hoped for, no one knew it at the time. Possibly were afraid of that possibility, but didn’t know for certain. And hoped their fears were wrong.

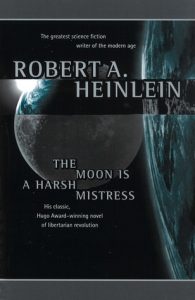

Another possibility thrown out was that Heinlein’s classic, and at the time relatively recent The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (1966), had, at least temporarily, taken all the air out of the fictional lunar room and no one wanted to jump in after the master. Even though Heinlein’s attitudes about women seem antediluvian 50 years later, I reread the thing not long ago and a surprising amount of it still holds up. And the ending still makes me tear up.

Another possibility thrown out was that Heinlein’s classic, and at the time relatively recent The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (1966), had, at least temporarily, taken all the air out of the fictional lunar room and no one wanted to jump in after the master. Even though Heinlein’s attitudes about women seem antediluvian 50 years later, I reread the thing not long ago and a surprising amount of it still holds up. And the ending still makes me tear up.

But the thing that struck me about this collection, particularly in contrast with some of Heinlein’s pre-Apollo lunar stories, not just Moon but also Gentlemen, Be Seated and even in a peculiar way The Man Who Sold the Moon, is just how dark the post-Apollo stories are in comparison to the pre-Apollo stories.

There was a lot of hope in those earlier stories. Not remotely scientifically based as we know now, but a buoyancy of spirit. We were going to get “out there” and it was going to be at least as good, if not better, than the present. Even if it took a revolution to get there.

Escape Rating B: The first several stories in this collection are seriously bleak. Either the moon is a wasteland, the Earth is, or both. Those dark futures probably mirror the state of the world at the time. Having lived through the 1970s, they seemed more hopeful in a lot of ways, but there were plenty of clouds were looming on the horizon – and some of those clouds were filled with acid rain.

And as far as the space program was concerned, all the air had been let out of its tires after the lunar landing. The uphill drive to reach the moon had been exhilarating, but the downhill slide was pretty grim.

A couple of the stories really got to me in their bleakness, A Walk in the Sun by Geoffrey A. Landis and Waging Good by Robert Reed.

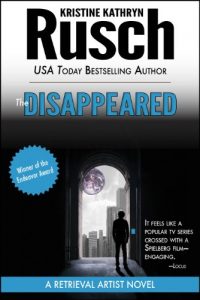

One of the other notable things about this collection is that, until Kristine Kathryn Rusch’s fascinating story, SeniorSource (2008), all of the stories were written by men. And that reflects the genre at the time. Female science fiction writers were thin on the ground until this century, as were writers of color – who are also singularly absent in the collection until that point.

I loved SeniorSource because it reminded me so much of the author’s Retrieval Artist series, which is also set on the moon (and which I now have a yen to reread). SeniorSource is a combination of SF with mystery, as is the Retrieval Artist series as a whole. But what I enjoyed about it in comparison with the earlier stories is that it’s a life goes on story. It’s set in a future that seems both plausible but not catastrophic. Life goes on, humans do human, and there is a future that is not bleak, but different.

I loved SeniorSource because it reminded me so much of the author’s Retrieval Artist series, which is also set on the moon (and which I now have a yen to reread). SeniorSource is a combination of SF with mystery, as is the Retrieval Artist series as a whole. But what I enjoyed about it in comparison with the earlier stories is that it’s a life goes on story. It’s set in a future that seems both plausible but not catastrophic. Life goes on, humans do human, and there is a future that is not bleak, but different.

From there the collection does look up. It’s an excellent sampling of post-Apollo lunar fiction, and a view of just how much the genre has changed over time. That being said, if you’re already blue, there’s a bit too much to depress you further in this book. But definitely an interesting read, and well worth savoring – possibly in bits to lighten the darkness a bit.