And now libraries know that Random House is planning to use real silver for that lining.

The problem with Random House’s plan is that libraries don’t have all that much silver to give them in this era of shrinking budgets.

On February 2, Random House, the only one of the “Big 6” publishers to provide ebooks to libraries without restrictions, made an announcement that they would continue their generous policy, but that there would be a price hike to deal with some of the issues surrounding permanent access to ebooks.

Most libraries probably expected the price to rise somewhere in the neighborhood of 50%. Maybe double.

The hammer fell March 1. Hammer as in auction hammer. Or the hammer of doom.

Yesterday, Random House tripled the prices of their ebooks. You read that right. An ebook that cost a library $15 on Monday, costs $45 today. The libraries are reeling from the sticker shock.

But what will this mean?

Library budgets are not growing, they are flat or shrinking. Public libraries are creatures of local government, and tax revenues at the local government level are still sucky. Let’s be blunt here.

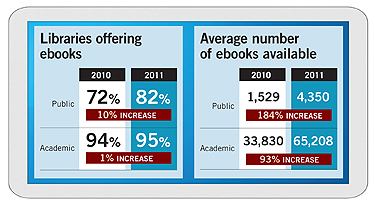

If the per-title price rises significantly, as it has just done. and the budget stays flat, what will happen? In most cases, libraries will buy fewer titles with the same dollars. Some will rearrange their budgets as much as they can, but very, very few will be able to triple their ebook budgets.

What gets purchased in this scenario? High-demand titles get purchased, so the hold queues get filled. Or at least stay tamed. John Grisham does not lose many library sales out of this.

What doesn’t get purchased? Mid-list authors and debut authors, because there is very little money left in the budget with which to take a chance. And the next John Grisham and Nora Roberts and James Patterson have to come from somewhere. Some of them will come from self-publication Cinderella stories like Amanda Hocking, but some will still come from the mid-list. If they get the chance.

Unlike V.C. Andrews, most authors do not write from beyond the grave. What are the publishers planning to do when the current crop of bestselling juggernauts decide to retire? The number one way that readers decide to purchase a book is because they liked the author’s last book. The trick seems to be to get people to read an author the first time. And with the demise of more and more bricks-and-mortar bookstores, that trick is getting harder all the time.

But protecting their authors is not what this move is about. Revenue numbers from 2011 are starting to come in from the major publishers, and the picture that emerges is very interesting. Sales of print are down, digital is up and profitability is up. Think about it for a minute. Digital books have no inventory, no print costs, and very low distribution costs. Most of the infrastructure to produce them already exists. For the publisher, they are almost pure profit.

Profitability is in no way a bad thing. It’s required for a business to remain in business. But let’s not pretend. Random House is charging more for their ebooks to libraries because Random House believes:

that pricing to libraries must account for the higher value of this institutional model, which permits e-books to be repeatedly circulated without limitation. The library e-book and the lending privileges it allows enables many more readers to enjoy that copy than a typical consumer copy. Therefore, Random House believes it has greater value, and should be priced accordingly.

In other words, because they can.

Scanning the fiction shelves of your local public library, there are a lot of books with labels on the spines for romance, mystery and science fiction. There’s at least one standard brand of those labels where the romance label was a heart, the mystery label was a dagger, and the sci-fi label was a spaceship.

Scanning the fiction shelves of your local public library, there are a lot of books with labels on the spines for romance, mystery and science fiction. There’s at least one standard brand of those labels where the romance label was a heart, the mystery label was a dagger, and the sci-fi label was a spaceship.

For those who missed the ALA Virtual Conference, the

For those who missed the ALA Virtual Conference, the