Freedom of Speech: Mightier Than the Sword by David K. Shipler

Freedom of Speech: Mightier Than the Sword by David K. Shipler Formats available: hardcover, paperback, ebook, audiobook

Pages: 352

Published by Knopf on May 12th 2015

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

A provocative, timely assessment of the state of free speech in America

With his best seller The Working Poor, Pulitzer Prize winner and former New York Times veteran David K. Shipler cemented his place among our most trenchant social commentators. Now he turns his incisive reporting to a critical American ideal: freedom of speech. Anchored in personal stories—sometimes shocking, sometimes absurd, sometimes dishearteningly familiar—Shipler’s investigations of the cultural limits on both expression and the willingness to listen build to expose troubling instabilities in the very foundations of our democracy.

Focusing on recent free speech controversies across the nation, Shipler maps a rapidly shifting topography of political and cultural norms: parents in Michigan rallying to teachers vilified for their reading lists; conservative ministers risking their churches’ tax-exempt status to preach politics from the pulpit; national security reporters using techniques more common in dictatorships to avoid leak prosecution; a Washington, D.C., Jewish theater’s struggle for creative control in the face of protests targeting productions critical of Israel; history teachers in Texas quietly bypassing a reactionary curriculum to give students access to unapproved perspectives; the mixed blessings of the Internet as a forum for dialogue about race.

These and other stories coalesce to reveal the systemic patterns of both suppression and opportunity that are making today a transitional moment for the future of one of our founding principles. Measured yet sweeping, Freedom of Speech brilliantly reveals the triumphs and challenges of defining and protecting the boundaries of free expression in modern America.

Most of the time, freedom of speech is an abstract concept. And even though it is enshrined in the Bill of Rights, the interpretation of what that simple phrase, “freedom of speech”, means in real life often depends on interpretation, and on which side of the current debate you might happen to be on.

The text in the U.S. Constitution reads as follows:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

One of the things that people often miss is that the direction of this law is to Congress. As written, it reflects the things that governments might want to do to us – it doesn’t actually address things that we might do to each other as private citizens.

There are a few legal restrictions on the freedom of speech, but there are many other ways to restrict speech. This book discusses real cases of where the freedom of speech has come under attack or into question, and by personalizing these stories provides a way for us to appreciate both the strengths and the limitations of those few brief words in the Constitution.

The author has grouped the situations where the “rubber meets the road” as far as free speech is concerned into some very challenging situations. The issues that he covers are: censorship, whistleblowing, bigotry, politics and culture. Because free speech is challenged in different ways and through different means in each of these instances.

One of the contradictions that is made unflinchingly clear, we may have freedom of speech, however, it may be abridged, or chilled or denied. What we don’t have (and generally shouldn’t) is the freedom from the consequences of that speech. And whether we like it or not, the challenges to our freedom of speech may very well be people who firmly believe that they are defending it.

Or us.

Reality Rating A: It’s the way that the author has personalized the abstract that brings this book to life. He doesn’t just talk in glowing platitudes about the freedom of speech, he takes deep dives into the hearts and minds who have fought, or are being fought, to protect or abridge that right.

And he also dissects some of the ways that free speech hurts, and why that makes it even more necessary.

The first section immediately drew me in, because it covered censorship, particularly as it applies to library book bannings and challenges. This is a subject with which I’m intimately familiar. At one of my former places of work, I was the person tasked with responding to challenges and overseeing the formation and the work of the staff assigned to serve on challenge committees and make recommendations.

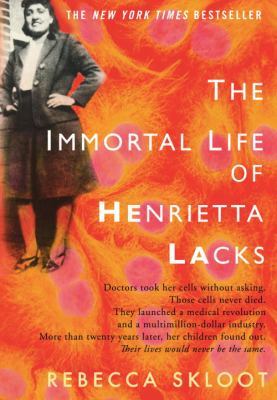

Even though this is Banned Books Week, the reality is that in today’s climate, books are challenged rather than banned. And it is generally books aimed at a teenage audience, although not always. As the author demonstrates by getting into the cases in Missouri (Slaughterhouse Five), Michigan (Waterland and Beloved), New York State (The Perks of Being a Wallflower, and practically everywhere (The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian). The late-breaking case about The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks in Tennessee shows that this is very much still happening. The one area where even childrens’ books get challenged is homosexuality, as the cases of Heather Has Two Mommies, And Tango Makes Three and Uncle Bobby’s Wedding make perfectly clear.

Even though this is Banned Books Week, the reality is that in today’s climate, books are challenged rather than banned. And it is generally books aimed at a teenage audience, although not always. As the author demonstrates by getting into the cases in Missouri (Slaughterhouse Five), Michigan (Waterland and Beloved), New York State (The Perks of Being a Wallflower, and practically everywhere (The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian). The late-breaking case about The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks in Tennessee shows that this is very much still happening. The one area where even childrens’ books get challenged is homosexuality, as the cases of Heather Has Two Mommies, And Tango Makes Three and Uncle Bobby’s Wedding make perfectly clear.

But in all these cases, the parental request is not to ban the book from the world, or even the U.S. This is impossible. But it generally comes down to “not their child” or “not for children” or “not at school”. They are often trying to maintain their child’s innocence just a little longer, and resent a school system that prefers to expose their children to what many people believe is the real world.

The striking thing is that such challenges always include the caveat that the person is not against freedom of speech, merely that this one thing, whatever it is, and whether they’ve read it or not, should not be protected, or that their children should be protected from it.

What is also clear in this section is that censorship can take many other, and more insidious, forms. Teachers in schools are unfortunately forced to teach to their state’s tests. And those tests can reflect biases and perspectives that support a political agenda or maintain the status quo. One of the big debates right now is about American exceptionalism and the beneficence of capitalism. Materials that do not reflect the desired perspective can be excised from the curriculum, and even where the teachers have limited freedom to teach from materials that are outside the curriculum, they may be squeezed out of those lessons by the unrelenting pressure of time to prepare their students for the tests.

Should we learn how the rest of the world views us while we are in high school, or should such knowledge wait until adulthood? Of course, with the prevalence of echo chambers on the internet, if we don’t seek out views that challenge our own, we may never find them.

The chapters on whistleblowers and the cost to those who choose to expose wrongdoing in organizations of which they are a part, especially when those organizations are the government, is chilling. The press may have freedom, and speech may be free, but the cost to individual whistleblowers is life-changing in a catastrophic way. And yet, a free society needs people who are willing to shine lights into dark places and risk the excoriation, persecution and sometimes prosecution that follows. By interviewing less famous whistleblowers, the author shines a light on how speech can be suppressed by the chilling effect of a threat to one’s job, one’s security, one’s personal freedom. And it gives us a little light into why people do it anyway.

Each section is like the two I have described. The author illustrates this abstract concept of freedom of speech by giving us real people and real situations to follow and empathize with. The sections on bigotry, hate speech and conspiracy theorists are particularly chilling, at least in part because those are areas we often feel squidgy about.

I found the last section particularly riveting. The story is about a very edgy artistic director at Theater J, an often flying-on-the-edge of controversy theater at the Jewish Community Center in Washington D.C. The art director put on challenging productions that often sold out, but equally often asked questions about Jewish themes and Israel’s place in the world and some of its past acts and policies that made some people very uncomfortable, out of a fear that questioning Israel’s actions might erode Israel’s U.S. support in Congress. The Q&A sessions after the productions were intellectually challenging and provocative. But because some of those plays shone a harsher light on some of Israel’s acts than certain conservative felt was desirable, there was a lot of push-back from potential donors to the Theater’s parent organization. We see the increasing pressure, as fears about money and perceptions that the Theater may be willing to go further out than its organization feels it can tolerate, create more and more artistic compromises. Speech may be free, but the cost to exercise it is not.

In writing this review, I took a look to see what had happened to the artistic director. He was fired, after 18 years as artistic director, because he wasn’t willing to back off from that intellectually challenging edge. He’s started another theater company elsewhere in DC, but his story shows that the cost of standing on that ledge of freedom of speech can be high.

If you are interested in putting human faces and voices to that abstract concept of freedom of speech, read this book.

Patience and Fortitude: Power, Real Estate, and the Fight to Save a Public Library by

Patience and Fortitude: Power, Real Estate, and the Fight to Save a Public Library by

The World Between Two Covers: Reading the Globe by

The World Between Two Covers: Reading the Globe by  The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by