President Johnson on July 4th, 1966, regarding the signing of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA):

THE MEASURE I sign today, S. 1160, revises section 3 of the Administrative Procedure Act to provide guidelines for the public availability of the records of Federal departments and agencies.

This legislation springs from one of our most essential principles: A democracy works best when the people have all the information that the security of the Nation permits. No one should be able to pull curtains of secrecy around decisions which can be revealed without injury to the public interest.

At the same time, the welfare of the Nation or the rights of individuals may require that some documents not be made available. As long as threats to peace exist, for example, there must be military secrets. A citizen must be able in confidence to complain to his Government and to provide information, just as he is–and should be–free to confide in the press without fear of reprisal or of being required to reveal or discuss his sources.

Fairness to individuals also requires that information accumulated in personnel files be protected from disclosure. Officials within Government must be able to communicate with one another fully and frankly without publicity. They cannot operate effectively if required to disclose information prematurely or to make public investigative files and internal instructions that guide them in arriving at their decisions.

I know that the sponsors of this bill recognize these important interests and intend to provide for both the need of the public for access to information and the need of Government to protect certain categories of information. Both are vital to the welfare of our people. Moreover, this bill in no way impairs the President’s power under our Constitution to provide for confidentiality when the national interest so requires. There are some who have expressed concern that the language of this bill will be construed in such a way as to impair Government operations. I do not share this concern.

I have always believed that freedom of information is so vital that only the national security, not the desire of public officials or private citizens, should determine when it must be restricted.

I am hopeful that the needs I have mentioned can be served by a constructive approach to the wording and spirit and legislative history of this measure. I am instructing every official in this administration to cooperate to this end and to make information available to the full extent consistent with individual privacy and with the national interest.

I signed this measure with a deep sense of pride that the United States is an open society in which the people’s right to know is cherished and guarded.

Despite the second and last paragraphs of this statement, Johnson was in fact far from a fan of FOIA. Per White House press secretary Bill Moyers, Johnson “had to be dragged kicking and screaming to the signing”. FOIA has had a checkered history over the years, but has enabled an unprecedented degree of transparency around government decisions, exemplified by the National Security Archive.

Freedom must be fought for every, but it is not just the result of stirring battles and speeches on the fields of sacrifice and victory. The quotidian matters as well: does this plan make sense? Do the numbers pencil out? Is the government correct in arresting this one individual or another? It is our responsibility as U.S. citizens to enact and protect our own freedom. Thus, a challenge for the year: are you confused about a government action? Disagree with it? Don’t just sit there: consider filing a FOIA request.

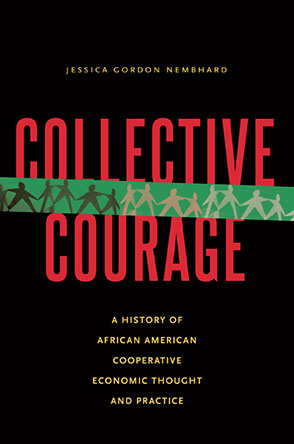

Today I purchased the book

Today I purchased the book