If one person in eight was known to be user of a particular service, would your library offer that service?

If one person in eight was known to be user of a particular service, would your library offer that service?

Let’s make some assumptions here, just to get the ball rolling. 1) The service is related to libraries’ core missions fairly closely, 2) That the figure of one person in eight applies nationwide, so there is a reason to believe it applies in your community, and 3) one person in eight is a rising tide, usage is measurably growing, and growing fast.

If the census showed that a particular demographic group had come to make up 12% or 13% of the population your library served, would you not immediately provide collections and services that targeted that group, if you had not already done so?

Now, what if I said that one user in three expected service to be provided to them in a particular way, would you provide service in that way? If you were a business, you would. But libraries are not businesses. Should we still provide services in the ways that people want them, instead of the ways that we are used to providing them? Those are the questions.

When these questions generally come up, the services and the delivery usually get mentioned first. This time, I talked about the numbers first, because the numbers are more important. The numbers represent people, and people are our users. Our users are our supporters, or, we want them to be. In order to keep their “mind-share” we need to provide service to them the ways they want and expect it, not just the ways we’re used to and are comfortable with.

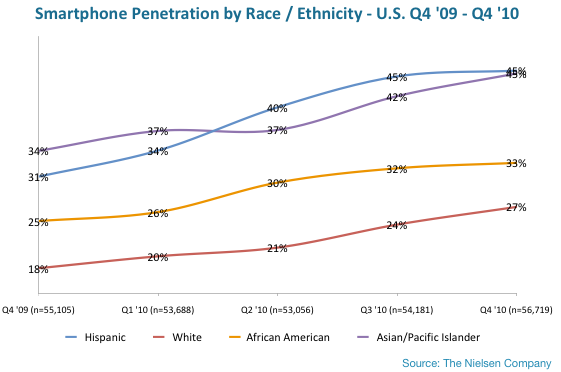

According to a recent (July 11, 2011) Pew International Report, 35% of all Americans have a smartphone. All Americans: not just teenagers and not just high-tech early adopters. According to studies done by Nielsen earlier this year, adoption rates for smartphones are high among all races and ethnic groups.

As the Pew Report found, people use their smartphones to surf the web, not just make phone calls. Two-thirds used their phones to search the internet every day. That means they expect to search for the library on their phone, not just on a computer, or maybe not at all on their computer. Are we optimized for that?

And about that one person in eight number, that’s from an “Infographic” created by Masters in Education on “Traditional Books vs. Digital Readers.” Statistics show that 12% of men and 11% of women owned a digital reader of some kind. Those statistics did not include smartphones, which are also capable of and are used as digital readers. One person in eight is searching for digital books for their ereaders, and that number is growing.

We want them to come to think of their library first. But in order for them to do that, we need to be thinking of them first, and we need to do it now.