Pistols and Petticoats: 175 Years of Lady Detectives in Fact and Fiction by Erika Janik

Pistols and Petticoats: 175 Years of Lady Detectives in Fact and Fiction by Erika Janik Formats available: hardcover, paperback, ebook

Pages: 248

Published by Beacon Press on April 26th 2016

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org

Goodreads

A lively exploration of the struggles faced by women in law enforcement and mystery fiction for the past 175 years

In 1910, Alice Wells took the oath to join the all-male Los Angeles Police Department. She wore no uniform, carried no weapon, and kept her badge stuffed in her pocketbook. She wasn’t the first or only policewoman, but she became the movement’s most visible voice.

Police work from its very beginning was considered a male domain, far too dangerous and rough for a respectable woman to even contemplate doing, much less take on as a profession. A policewoman worked outside the home, walking dangerous city streets late at night to confront burglars, drunks, scam artists, and prostitutes. To solve crimes, she observed, collected evidence, and used reason and logic—traits typically associated with men. And most controversially of all, she had a purpose separate from her husband, children, and home. Women who donned the badge faced harassment and discrimination. It would take more than seventy years for women to enter the force as full-fledged officers.

Yet within the covers of popular fiction, women not only wrote mysteries but also created female characters that handily solved crimes. Smart, independent, and courageous, these nineteenth- and early twentieth-century female sleuths (including a healthy number created by male writers) set the stage for Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, Sara Paretsky’s V. I. Warshawski, Patricia Cornwell’s Kay Scarpetta, and Sue Grafton’s Kinsey Millhone, as well as TV detectives such as Prime Suspect’s Jane Tennison and Law and Order’s Olivia Benson. The authors were not amateurs dabbling in detection but professional writers who helped define the genre and competed with men, often to greater success.

Pistols and Petticoats tells the story of women’s very early place in crime fiction and their public crusade to transform policing. Whether real or fictional, investigating women were nearly always at odds with society. Most women refused to let that stop them, paving the way to a modern professional life for women on the force and in popular culture.

My Review:

I want to make a joke about Pistols and Petticoats being “two, two, two books in one”, but the problem with the book is that it isn’t. Instead it is two books that attempt to be combined into one. Unfortunately the seam between the two books is rather visible, and leaves a nasty and distinguishing scar.

What we have feels like an attempt to yoke a scholarly study about the changing roles of women in detection and police work joined at the slightly non-working hip with a book about the changing roles of women in detective fiction and the lives and careers of women who have made successful and even groundbreaking forays into the mystery genre.

The desire, often stated in the book, is to show how the increased roles of women in novels and later other media often presaged the increasing roles for women in real-life police work. But the two parts don’t flow into one another, possibly because there isn’t much there, well, there.

Instead, in the historical narrative, police work for women was often proposed as, and in many cases restricted to, an extension of the reform zeal of the late 1800s and the belief that dealing with social problems and juvenile crime were a natural outgrowth of women’s roles in the home. Fictional female sleuths, on the other hand, were created first of all to entertain, but created in a way that was not supposed to upset the status quo. Which explains both Miss Marple and the reason that so many young female sleuths’ careers ended in marriage.

Women were supposed to remain in the domestic sphere, and that sphere was supposed to be the pinnacle of all their ambitions. Elderly spinsters like Miss Marple needed something to occupy their time, particularly in eras where so many women were left without spouses after a generation of young men died in warfare.

Pistols and Petticoats does not read like a successful amalgamation of the author’s two “plot” lines. The historical sections that detail women’s real and increasing contributions to police work and detection, read, unfortunately, like rather dry history. It’s interesting, but only becomes lively when the women themselves have interesting lives, like Alice Clement or Kate Warne.

The parts that thrill are where the author sinks her teeth into the history of female detectives and the history of the females who have written successful mysteries. The early years of female writers who made the genre what it is today, but whose works have not continued to find readers, was fascinating.

The information about where certain trends in mystery took their cues from contemporary life and women’s places in it also pulled me in. Not just the heroines of the Golden Age, like Christie and Marple, and Sayers with Harriet Vane, but also how those characters fit into their own society.

Escape Rating C+: All in all, the parts of the book that dealt with mystery fiction made for more compelling reading. They also reminded me of a book that I have not thought of in years, Murderess Ink. Murderess Ink, the followup to Murder Ink, was a lighthearted study of the women who created and populated the mystery genre from the Golden Age until its late 1970s present. As much as I enjoyed the sections of Pistols and Petticoats that dealt with the genre, perhaps it is time for an update of Murder Ink and Murderess Ink.

Escape Rating C+: All in all, the parts of the book that dealt with mystery fiction made for more compelling reading. They also reminded me of a book that I have not thought of in years, Murderess Ink. Murderess Ink, the followup to Murder Ink, was a lighthearted study of the women who created and populated the mystery genre from the Golden Age until its late 1970s present. As much as I enjoyed the sections of Pistols and Petticoats that dealt with the genre, perhaps it is time for an update of Murder Ink and Murderess Ink.

Terrible Virtue by

Terrible Virtue by

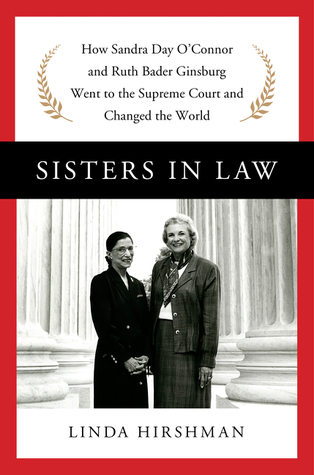

Sisters in Law: Sandra Day O'Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and the Friendship That Changed Everything by

Sisters in Law: Sandra Day O'Connor, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and the Friendship That Changed Everything by