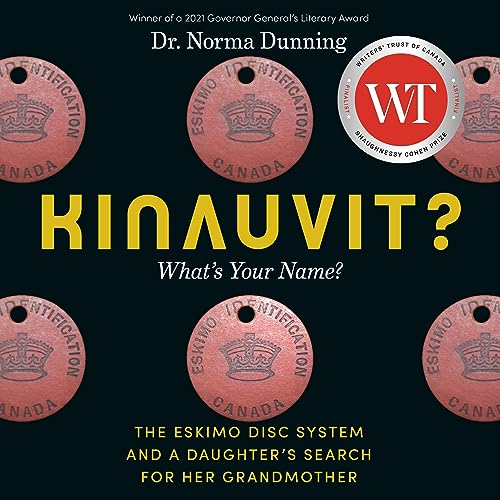

Kinauvit?: What's Your Name? The Eskimo Disc System and a Daughter's Search for her Grandmother by Norma Dunning

Kinauvit?: What's Your Name? The Eskimo Disc System and a Daughter's Search for her Grandmother by Norma Dunning Narrator: Norma Dunning

Format: audiobook, eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via Edelweiss, supplied by publisher via Libro.fm

Formats available: hardcover, ebook, audiobook

Genres: Canadian history, history, memoir

Pages: 184

Length: 6 hours and 4 minutes

on August 1, 2023

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Better World Books

Goodreads

From the winner of the 2021 Governor General's Award for literature, a revelatory look into an obscured piece of Canadian history: what was then called the Eskimo Identification Tag System

In 2001, Dr. Norma Dunning applied to the Nunavut Beneficiary program, requesting enrolment to legally solidify her existence as an Inuk woman. But in the process, she was faced with a question she could not answer, tied to a colonial institution retired decades ago: "What was your disc number?"

Still haunted by this question years later, Dunning took it upon herself to reach out to Inuit community members who experienced the Eskimo Identification Tag System first-hand, providing vital perspective and nuance to the scant records available on the subject. Written with incisive detail and passion, Dunning provides readers with a comprehensive look into a bureaucracy sustained by the Canadian government for over thirty years, neglected by history books but with lasting echoes revealed in Dunning's intimate interviews with affected community members. Not one government has taken responsibility or apologized for the E-number system to date -- a symbol of the blatant dehumanizing treatment of the smallest Indigenous population in Canada.

A necessary and timely offering, Kinauvit? provides a critical record and response to a significant piece of Canadian history, collecting years of research, interviews and personal stories from an important voice in Canadian literature.

My Review:

The title of this book is a question, because that’s how this author’s journey began. While it begins as a reclamation of identity, what that attempt leads to is a search for it – or at least, and with full irony as becomes apparent during the telling – a search for a very specific piece of government documentation that was intended, not to confirm but rather to deny the lived essence of an identity it was designed to repress if not, outright, erase.

That search for proof of her mother’s, and as a result her own, Inuit heritage led the author, not just to a multi-year search but also to a second act career in academia, exposing the origins and the abuses – whether committed out of governmental malice or idiocy – of a system that may have been claimed to be a system for identifying the Inuit population, but was truly intended to colonize them, divide them, and ultimately erase the beliefs and practices that made them who they were.

So on the one hand, this is a very personal story. The author had learned only in adulthood that she was, herself, Inuit. It’s a truth that her own mother refused to talk about as long as she lived. But when Dunning decided to apply for enrolment in the Nunavut Beneficiary program, she opened up the proverbial can of worms, discovering long-buried secrets that had overshadowed her mother’s life and the lives of all Inuit of her mother’s generation and the one before it. A history that was as poorly documented as her mother’s life and identity.

It’s a journey that began with a hope, middled with a question that turned into an obsession – even after that hope was answered – and led to the author’s search for a history that was long-denied but that needed to be brought into the light.

Reality Rating C: Kinauvit? is a combination of a personal search for identity with the intricacies of searching in records that were an afterthought for the government that recorded them, administered them and was, at least in theory, supposed to serve the people those records concerned but that the government obviously didn’t understand a whit. But the story of that personal search is mixed, but not terribly well blended, with a scholarly paper about the history of the Canadian government’s treatment and suppression of the Inuit peoples over whom the government believed it held sovereignty.

The two narratives, the author’s personal search and the scholarly paper that resulted from it (her Master’s thesis for the University of Alberta) both have important stories to tell, and either had the possibility of carrying this book. The issue is that the two purposes don’t blend together, but rather march along side-by-side uncomfortably and unharmoniously as they are entirely different in structure and tone to the point where they don’t reinforce each other’s message the way that they should – or was mostly likely intended that they should.

This book contains just the kind of hidden history that cries out to be revealed. But this attempt to wrap the personal journey around the academic paper results in a book that doesn’t quite work for either of its prospective audiences.

I listened to Kinauvit? in audio, which generally works well for me for first-person narratives, which this looked like it would be. Also, sometimes an excellent reader can carry a book over any rough patches in its text, especially for a work with a compelling story or an important topic that I have a strong desire to see revealed. Kinauvit? as an audiobook had both of the latter, a search that was compelling, combined with a deep dive into historical archives which is absolutely my jam, resulting in a true story of government neglect and outright stupidity.

But it is very, very rare that authors turn out to be good readers for their work unless they have some kind of performance experience. In all of the audiobooks I have ever listened to over the past three decades, I can only think of one exception to serve as an exception.

In this particular case, the author recites the book as though she was delivering the academic paper that forms the core of the book. But this publication of the work was not intended to BE an academic paper. The audience for this work would be better served with a narrator who is able to ‘voice’ the book, to use a narrative style imbued with the flow and the cadences of a storyteller.

The dry recitation that I listened to blunted the impact of the personal side of the story while the inclusion of the words “Footnote 1”, “Footnote 2”, etc., when one of the many, many footnotes occurred in the text was jarring to the point that it broke this reader out of the book completely. That the footnotes themselves consisted of the simple reference to the place in the source material from which the quote was drawn added nothing to the narrative but made its origin as a scholarly paper all too apparent.

In the end, this book left me torn. I wanted to love it. I was fascinated by its premise, and remain so. It’s important history and not just Canadian history. The truths that the author uncovered deserve a wider audience and more official recognition than has been achieved to date. But this vehicle for telling those truths doesn’t do them justice, even though justice is exactly what is needed.