Queen Macbeth by Val McDermid

Queen Macbeth by Val McDermid Format: eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via Edelweiss

Formats available: hardcover, ebook, audiobook

Genres: historical fiction, retellings, Scottish history

Series: Darkland Tales #5

Pages: 144

Published by Atlantic Monthly Press on September 24, 2024

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org, Better World Books

Goodreads

Shakespeare fed us the myth of the Macbeths as murderous conspirators. But now Val McDermid drags the truth out of the shadows, exposing the patriarchal prejudices of history. Expect the unexpected . . .

A thousand years ago in an ancient Scottish landscape, a woman is on the run with her three companions – a healer, a weaver and a seer. The men hunting her will kill her – because she is the only one who stands between them and their violent ambition. She is no lady: she is the first queen of Scotland, married to a king called Macbeth.

As the net closes in, we discover a tale of passion, forced marriage, bloody massacre and the harsh realities of medieval Scotland. At the heart of it is one strong, charismatic woman, who survived loss and jeopardy to outwit the endless plotting of a string of ruthless and power-hungry men. Her struggle won her a country. But now it could cost her life.

My Review:

Shakespeare, for the most part, did an excellent job of writing stories that made an indelible imprint on the public consciousness – and still do. It’s pretty much impossible to hear the name “Macbeth” and not think of the version of both the title character AND his lady as ambitious traitors and multiple murderers driven by supernatural forces and haunted by ghosts.

Just as it’s nearly impossible to think of Richard III without having Shakespeare’s portrayal of an evil mastermind who killed his nephews and lost his crown – in spite of the evidence that has come to light refuting nearly all of it.

Shakespeare’s stories are just better, and considerably more memorable than the actual tales that history tells. Whoever he was, he was damn good at his job. Part of which was to please the powers-that-be of his day, so that his plays could continue to be produced and performed – and so that he could keep himself out of prison and his head attached to his shoulders.

Which is where the genesis of many of Shakespeare’s historical plays, including both of the above, comes in. Just as Richard III was a real, historical figure in English history, so too was Macbeth a real, historical figure of Scottish history.

A figure about whom little is known, because the historical Macbeth lived in the early to mid-11th century and there isn’t much in the historic record. Probably something to do with that being the historical period known as “The Dark Ages”.

Shakespeare lived, and wrote, in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, nearly 600 years later. He based many of his historical plays on Holinshed’s Chronicles, a famous – but later considered infamously inaccurate – ‘comprehensive’ history that was published in Shakespeare’s time.

In other words, Shakespeare made a lot of things up, and a lot of the things he didn’t make up were based on the things that Holinshed made up.

Which is precisely where this retelling of the Macbeth story comes in, told not from Macbeth’s perspective or even featuring Macbeth as the central character, but instead told from the perspective of Gruoch, Macbeth’s, ‘lady’, or more historically correct, his ‘queen’.

Although, as seen from this point of view, it seems that Gruoch may have been the prime mover of events after all, with the help of her own coven of ‘witches’. Which may explain precisely why Shakespeare reduced her to a secondary character – and a villainous one at that.

Escape Rating A-: I picked up Queen Macbeth because this is the second retelling of the Macbeth story from Gruoch’s perspective, set in something much closer to the historical context, to be published this year. The other being Lady Macbeth by Ava Reid.

Escape Rating A-: I picked up Queen Macbeth because this is the second retelling of the Macbeth story from Gruoch’s perspective, set in something much closer to the historical context, to be published this year. The other being Lady Macbeth by Ava Reid.

While the two books come out of very similar premises, they surprisingly don’t resemble each other at all. Lady Macbeth leans quite a bit on the supernatural/paranormal potential that derives from Shakespeare’s version, with family curses and chained witches and imprisoned seers – with a dragon lover as Gruoch’s reward for dealing with Macbeth. Her version makes Macbeth the villain and Gruoch a victim who finally takes matters into her own hands.

This version, Queen Macbeth (which I personally liked a bit better), hews closer to what is known about the historical figures and the original time period. Gruoch and her ladies are always in danger of being called out as witches, but their witchcraft is of the herbal, medicinal and occasionally poisonous variety. One seems to have visions of the future that often, but not always, come true – but that’s as far as the supernatural element seems to go.

Mostly, it’s that Gruoch and her women are intelligent, educated and independent, and as is known from the witch trials of centuries later, that’s was often all it took for women to be condemned as ‘unnatural’ and in league with the forces of evil.

The story of this Gruoch and her Macbeth tells a story of political machinations, true partnership and enduring romance – even as it includes a happy ever after, of a sort, that is plausible based on what is known but unlikely – and makes for a satisfying, if somewhat open ended, conclusion for the reader.

Howsomever, as little as this version of the Macbeth story owes to Shakespeare, in the reading of it it seems to owe considerably more to a different chronicler. Specifically, this reader at least saw a lot of resemblance to Guinevere’s story in Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (The Death of Arthur). Although, again, with a considerably happier ending, if only because there’s neither a Lancelot or a Mordred to mess things up.

I’m aware that I keep talking ‘around’ this story instead of ‘about’ this story because a) it’s not exactly new, it’s part of the literary trend of telling classic stories from a female perspective that was popularized by Madeline Miller’s Circe a few years back, and 2) the circumstances that surround this particular participant in that trend grabbed me more than the story itself. A fascination that only grew when I learned that this book is the latest in a series of Darkland Tales, which reexamine and even re-imagine some of the darkest chapters of Scottish history by 21st century writers. The other stories in this series so far, Rizzio by Denise Mina, Hex by Jenni Fagan, Nothing Left to Fear from Hell by Alan Warner, and Columba’s Bones by David Greig, all intrigue me, but particularly Rizzio with its connections to the court of Mary, Queen of Scots.

I’m aware that I keep talking ‘around’ this story instead of ‘about’ this story because a) it’s not exactly new, it’s part of the literary trend of telling classic stories from a female perspective that was popularized by Madeline Miller’s Circe a few years back, and 2) the circumstances that surround this particular participant in that trend grabbed me more than the story itself. A fascination that only grew when I learned that this book is the latest in a series of Darkland Tales, which reexamine and even re-imagine some of the darkest chapters of Scottish history by 21st century writers. The other stories in this series so far, Rizzio by Denise Mina, Hex by Jenni Fagan, Nothing Left to Fear from Hell by Alan Warner, and Columba’s Bones by David Greig, all intrigue me, but particularly Rizzio with its connections to the court of Mary, Queen of Scots.

They all look like stories to turn to on a dark and stormy night, and I plan to do exactly that when the mood strikes.

Lady Macbeth by

Lady Macbeth by

(If you’re wondering – as I was – it reminds me of

(If you’re wondering – as I was – it reminds me of  A Sorceress Comes to Call by

A Sorceress Comes to Call by  Escape Rating A+: This wasn’t what I expected, although having read quite a bit of the author’s work, I probably should have.

Escape Rating A+: This wasn’t what I expected, although having read quite a bit of the author’s work, I probably should have.  Which is when I felt like I got hit with a clue-by-four, to the point of chagrin that I didn’t figure out a whole bunch of things sooner. Not the way that Hester got the best of the sorceress, but rather the way that the story as a whole worked. And, as I mulled things over more than a bit, the way that

Which is when I felt like I got hit with a clue-by-four, to the point of chagrin that I didn’t figure out a whole bunch of things sooner. Not the way that Hester got the best of the sorceress, but rather the way that the story as a whole worked. And, as I mulled things over more than a bit, the way that  Daughters of Olympus by

Daughters of Olympus by  Lost Ark Dreaming by

Lost Ark Dreaming by  The Scandalous Confessions of Lydia Bennet, Witch by

The Scandalous Confessions of Lydia Bennet, Witch by  Escape Rating B: This wants to be Lydia Bennet’s redemption story. Or rather, the way it’s written, as Lydia’s confessional to an initially unnamed party, Lydia thinks it’s her redemption story when it’s actually not. It IS a confession, of sorts, but it’s a self-justification story. It’s her long-winded explanation of everything that happened and why it happened the way it did. It’s her attempt to win forgiveness. A forgiveness she only proves herself deserving of when she DOESN’T send the damn thing.

Escape Rating B: This wants to be Lydia Bennet’s redemption story. Or rather, the way it’s written, as Lydia’s confessional to an initially unnamed party, Lydia thinks it’s her redemption story when it’s actually not. It IS a confession, of sorts, but it’s a self-justification story. It’s her long-winded explanation of everything that happened and why it happened the way it did. It’s her attempt to win forgiveness. A forgiveness she only proves herself deserving of when she DOESN’T send the damn thing.

Thornhedge by

Thornhedge by  Escape Rating A: Thornhedge is a fractured fairy tale. In fact, Thornhedge and

Escape Rating A: Thornhedge is a fractured fairy tale. In fact, Thornhedge and  The Cleaving by

The Cleaving by

White Cat, Black Dog: Stories by

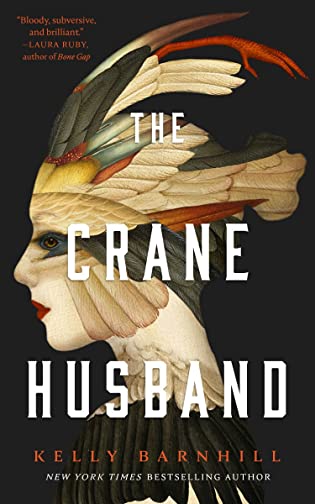

White Cat, Black Dog: Stories by  The Crane Husband by

The Crane Husband by