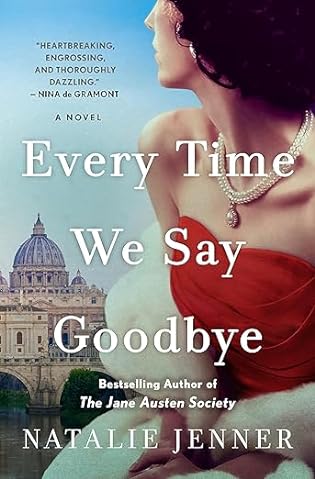

Every Time We Say Goodbye (Jane Austen Society, #3) by Natalie Jenner

Every Time We Say Goodbye (Jane Austen Society, #3) by Natalie Jenner Narrator: Juliet Aubrey

Format: audiobook, eARC

Source: supplied by publisher via NetGalley

Formats available: hardcover, ebook, audiobook

Genres: historical fiction, World War II

Series: Jane Austen Society #3

Pages: 336

Length: 10 hours and 37 minutes

Published by Macmillan Audio, St. Martin's Press on May 14, 2024

Purchasing Info: Author's Website, Publisher's Website, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Kobo, Bookshop.org, Better World Books

Goodreads

The bestselling author of The Jane Austen Society and Bloomsbury Girls returns with a brilliant novel of love and art, of grief and memory, of confronting the past and facing the future.

In 1955, Vivien Lowry is facing the greatest challenge of her life. Her latest play, the only female-authored play on the London stage that season, has opened in the West End to rapturous applause from the audience. The reviewers, however, are not as impressed as the playgoers and their savage notices not only shut down the play but ruin Lowry's last chance for a dramatic career. With her future in London not looking bright, at the suggestion of her friend, Peggy Guggenheim, Vivien takes a job in as a script doctor on a major film shooting in Rome’s Cinecitta Studios. There she finds a vibrant movie making scene filled with rising stars, acclaimed directors, and famous actors in a country that is torn between its past and its potentially bright future, between the liberation of the post-war cinema and the restrictions of the Catholic Church that permeates the very soul of Italy.

As Vivien tries to forge a new future for herself, she also must face the long-buried truth of the recent World War and the mystery of what really happened to her deceased fiancé. Every Time We Say Goodbye is a brilliant exploration of trauma and tragedy, hope and renewal, filled with dazzling characters both real and imaginary, from the incomparable author who charmed the world with her novels The Jane Austen Society and Bloomsbury Girls.

My Review:

I picked this up because I loved the author’s earlier book, The Jane Austen Society, and hoped for more of the same. Which I got in a couple of surprising ways. First, part of my love for that first book was in the audiobook narrator, Richard Armitage (yes, Thorin Oakenshield from The Hobbit movies). Second, that this book is loosely connected to both that book and to her second book, Bloomsbury Girls, but it’s a loose connection and you absolutely do not need to have read either of the others to get into this one.

I picked this up because I loved the author’s earlier book, The Jane Austen Society, and hoped for more of the same. Which I got in a couple of surprising ways. First, part of my love for that first book was in the audiobook narrator, Richard Armitage (yes, Thorin Oakenshield from The Hobbit movies). Second, that this book is loosely connected to both that book and to her second book, Bloomsbury Girls, but it’s a loose connection and you absolutely do not need to have read either of the others to get into this one.

The first goodbye in Every Time We Say Goodbye takes place in 1943, in Occupied Italy during the midst of World War II. It’s the final goodbye between the infamous ‘La Scolaretta’, AKA the ‘Schoolgirl Assassin’, and her lover after she has committed the assassination that both ensures her immediate death and her eternal ‘life’ as a martyr to the cause..

The rest of the story spirals out from that first/last goodbye – and moves forward to 1955 even as it circles back to Rome, the scene of La Scolaretta’s last and most dangerous assignment. It’s a world that is doing its best to move on and forget – even as entirely too many people’s lives seem to be frozen in that moment – or in moments much too much like it.

On the surface of this story, there’s glitz and glamour, the escape of the movie industry and the films it produces – along with the kind of frenetic partying that drove the Jazz Age of the 1920s – another post-war era.

Vivien Lowry has brought herself and her heavy emotional baggage from London to Rome, to escape the failure of her latest play on the London stage by taking a job as a ‘script doctor’ to American ex-pats filming in Italy to escape the political witch hunts back home.

She is also in Italy to say her own final goodbyes – if she can find a place to actually do that. Her fiance was presumed killed in action in the war, but late news has reached her that he was transported to Italy as a POW and died in a POW camp or escaping from it and not on the battlefield as was originally supposed. Or maybe he didn’t.

Vivien is tracking down the shattered remnants of her heart, so she can bury them along with the hopes and dreams of the future that they represent. Along the way, she meets the glitterati of the heyday of Italian movie making, while dropping a whole lot of very real names of the rich and famous.

And she falls in love. Or maybe she doesn’t. She certainly gets caught up in a relationship that is going absolutely nowhere – only to discover that her lover isn’t the man he pretended to be. Then again, she pretended that her heart was open, when it’s still buried in a past that never was – and never will be again, now matter how hard she chases after it.

But it just might manage to catch up with her if she stops running long enough to let it.

Escape Rating B: Before I get to the story of the book, I absolutely need to say something about the audiobook. Specifically, that the audiobook is excellent. The reader, Juliet Aubrey, was a perfect choice and she made the whole thing better and carried me through even at points where I wondered how the parts of the story connected to each other because she was just awesome.

Escape Rating B: Before I get to the story of the book, I absolutely need to say something about the audiobook. Specifically, that the audiobook is excellent. The reader, Juliet Aubrey, was a perfect choice and she made the whole thing better and carried me through even at points where I wondered how the parts of the story connected to each other because she was just awesome.

Which circles back to the story itself, which sometimes felt as if it, well, didn’t exactly circle back and connect up. So the TL;DR version of this review is that, as a story, its reach very much exceeded its grasp.

There is, of course, a much longer version of that, because there is a tremendous amount going on in this story with a corresponding large cast of characters.

There are two timelines, and the reader keeps wondering how they’re going to come together in the end – only for this reader, at least, to wish they hadn’t.

Yes, I know my flailing is getting worse. But it fits.

The through story, the one we’re following, takes place in Rome in 1955 at what may have been the height of the Italian film industry. The story that they, the characters in the story, are following is the 1943 story about the famous and/or infamous guerilla fighter, La Scolaretta – the schoolgirl assassin.

The characters in 1955 are living their current lives following that story because they are writing it, filming it, still affected by it, still suffering from it, still mourning it, unable to get past it and/or absolutely all of the above.

La Scolaretta’s last target, and her subsequent capture, torture and execution, is a fixed point in time that no one can walk past or turn away from. Both for itself and as a symbol of the war and the acts that people were driven to during it.

As a consequence, the story has a LOT to say about war in general, World War II in particular, the evils that humans generally and specifically did as a result of both of them, as well as guilt, grief, escape, survival, life, death and how all of those things are impacted by survival.

It’s a lot of weight for one story to carry, and these characters, especially Vivien Lowry as the point-of-view character, have a lot to say about all of them, which leads to a lot of justified angst and downright philosophizing on her part that suffuses the whole story.

But the philosophizing also got in the way of the story – possibly as intended because Vivien, as a writer herself, doesn’t so much experience her own emotions as she does explain them or distance them through her writing.

(In addition to Vivien’s personal angsting and philosophizing, the story also had a TON of things to say about the conflict between the need of certain institutions to rug-sweep their activities during the war, the desire of governments and individuals to put the war behind them as quickly as possible, the human desire to leave the tragedy behind vs the need to record and remember everything that happened in the hopes of staving the tragedy off earlier the next time around, AND, on top of all that, foreshadowing the cultural upheavals of the 1960s. It was a LOT and the story was already a LOT and we’re back to the reach exceeding the grasp again. All of the issues the story touched on were important but maybe they didn’t need to all be in the same book. Or the book needed to be an actual trilogy – at least.)

So as much as I felt compelled to finish the story (and I was absolutely riveted most of the way through) to see if the past directly connected to their present – or if it just exposed it or talked around it. Which it didn’t quite in either direction. But it did seem like it came to a kind of a satisfactory conclusion even if Vivien’s happy ever after came a bit out of the blue. She still found closure for as much of her past as was possible.

But we didn’t. The conclusion we thought we had got pulled out from under the reader in the end – and I was left wishing it hadn’t. OTOH, war doesn’t really have any neat and tidy endings either, and perhaps that was the point after all.

.

.

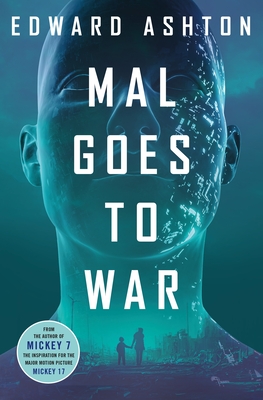

Mal Goes to War by

Mal Goes to War by  Because Mal isn’t human at all. He’s a free A.I., or as his people prefer to be called, a Silico-American. He’s merely observing this stupid war from the perspective of an otherwise fairly autonomous but not intelligent drone when he gets the wild and crazy idea to see what it would be like to have a body.

Because Mal isn’t human at all. He’s a free A.I., or as his people prefer to be called, a Silico-American. He’s merely observing this stupid war from the perspective of an otherwise fairly autonomous but not intelligent drone when he gets the wild and crazy idea to see what it would be like to have a body. What hooks the reader, or at least this reader, from the very first page is Mal’s conversation with his two fellow A.I.s, Clippy and !HelpDesk. They’re all snarky to the max, and none of them think much of humanity. To them, we’re entertainment – and we’re bad, boring entertainment at that.

What hooks the reader, or at least this reader, from the very first page is Mal’s conversation with his two fellow A.I.s, Clippy and !HelpDesk. They’re all snarky to the max, and none of them think much of humanity. To them, we’re entertainment – and we’re bad, boring entertainment at that. Random in Death (In Death, #58) by

Random in Death (In Death, #58) by  Escape Rating B: Learning how all my ‘book friends’ were doing in this latest entry in the

Escape Rating B: Learning how all my ‘book friends’ were doing in this latest entry in the  Payback in Death (In Death, #57) by

Payback in Death (In Death, #57) by  Escape Rating B: At this point, I’m here to see how all my ‘book friends’ are doing after whatever happened in the previous book in the series (which in this case was

Escape Rating B: At this point, I’m here to see how all my ‘book friends’ are doing after whatever happened in the previous book in the series (which in this case was  And that the investigation displayed yet again the reasons that Dallas and her squad are the best at what they do.

And that the investigation displayed yet again the reasons that Dallas and her squad are the best at what they do. Encore in Death (In Death, #56) by

Encore in Death (In Death, #56) by  Figuring out what those ‘marriage rules’ are in her own marriage is a work in progress for Dallas. She expected to go through life alone – she certainly never expected to fall in love and get married to anyone, let alone to an ex-thief turned business mogul. All of which is pretty much the story of the entire

Figuring out what those ‘marriage rules’ are in her own marriage is a work in progress for Dallas. She expected to go through life alone – she certainly never expected to fall in love and get married to anyone, let alone to an ex-thief turned business mogul. All of which is pretty much the story of the entire  All things considered, however, this isn’t one of the great cases in Dallas’ career – not nearly as absorbing in itself as last year’s

All things considered, however, this isn’t one of the great cases in Dallas’ career – not nearly as absorbing in itself as last year’s  Desperation in Death (In Death, #55) by

Desperation in Death (In Death, #55) by  The desperation that leads to the death that brings Eve Dallas and her ever-expanding crew onto this case is one that Eve is entirely too familiar with. It’s the desperation of a girl who has been trapped into a life where she is merely an object for other people’s abuse and other people’s pleasure.

The desperation that leads to the death that brings Eve Dallas and her ever-expanding crew onto this case is one that Eve is entirely too familiar with. It’s the desperation of a girl who has been trapped into a life where she is merely an object for other people’s abuse and other people’s pleasure. All of that is a way to loop back around and say this is a solid and solidly entertaining entry in the series for long-time fans. If you love Dallas and Roarke you’ll enjoy this season’s peek into their lives as much as I did.

All of that is a way to loop back around and say this is a solid and solidly entertaining entry in the series for long-time fans. If you love Dallas and Roarke you’ll enjoy this season’s peek into their lives as much as I did. The Bodyguard by

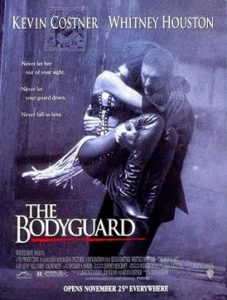

The Bodyguard by  It’s not exactly a surprise that this a bodyguard romance. After all, the title does pretty much give it away. But before your head starts playing “I Will Always Love You” on endless repeats, this book’s version of that popular trope would have Whitney Houston guarding Kevin Costner. Which is more than a bit of a twist, at least if that’s the picture you have in your head.

It’s not exactly a surprise that this a bodyguard romance. After all, the title does pretty much give it away. But before your head starts playing “I Will Always Love You” on endless repeats, this book’s version of that popular trope would have Whitney Houston guarding Kevin Costner. Which is more than a bit of a twist, at least if that’s the picture you have in your head. Escape Rating B-: This is a story where I had both the audiobook and the ebook, which means I started by listening to the audiobook. I switched to the ebook at less than a third of the way through – not because I was impatient to see what happened next but because the audio was driving me utterly bonkers.

Escape Rating B-: This is a story where I had both the audiobook and the ebook, which means I started by listening to the audiobook. I switched to the ebook at less than a third of the way through – not because I was impatient to see what happened next but because the audio was driving me utterly bonkers. Road of Bones by

Road of Bones by  Escape Rating A-: I was willing to take this chilling drive into horror because of the author. Christopher Golden, along with Tim Lebbon, wrote one of the most haunting post-Katrina New Orleans stories to ever ride that slippery line between fantasy, history, myth and horror in

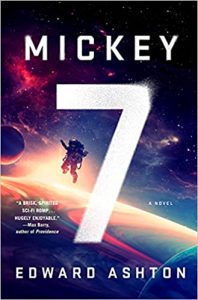

Escape Rating A-: I was willing to take this chilling drive into horror because of the author. Christopher Golden, along with Tim Lebbon, wrote one of the most haunting post-Katrina New Orleans stories to ever ride that slippery line between fantasy, history, myth and horror in  Mickey7 by

Mickey7 by  Mickey’s issues are the same ones dealt with in

Mickey’s issues are the same ones dealt with in  Abandoned in Death (In Death, #54) by

Abandoned in Death (In Death, #54) by